6 things you should know about plantar fasciitis

Summary

Plantar fasciitis (PF) is an overuse injury characterised by repeated trauma to the plantar fascia, usually at the origin, the medial calcaneus tuberosity. In this post we review the plantar fascia, its function, causes of injury to this tissue and treatment options.

Table of contents:

– Intoduction – Thing 1 – what is the plantar fascia? – Thing 2 – what is the function of the plantar fascia? – Thing 3 – What exactly is plantar fasciitis? – Thing 4 – what makes the fascia prone to tearing? – Thing 5 – How is plantar fasciitis diagnosed? – Thing 6 – Treatment options for plantar fasciitis? – References

Nuno Gama, PhD

Nuno is passionate about science, sports, his family

and dogs. He currently rides a Fuji one.1 equipped

with Ultegra and Mavic Cosmic carbon pro.

Introduction

Thing 1 - What is the plantar fascia?

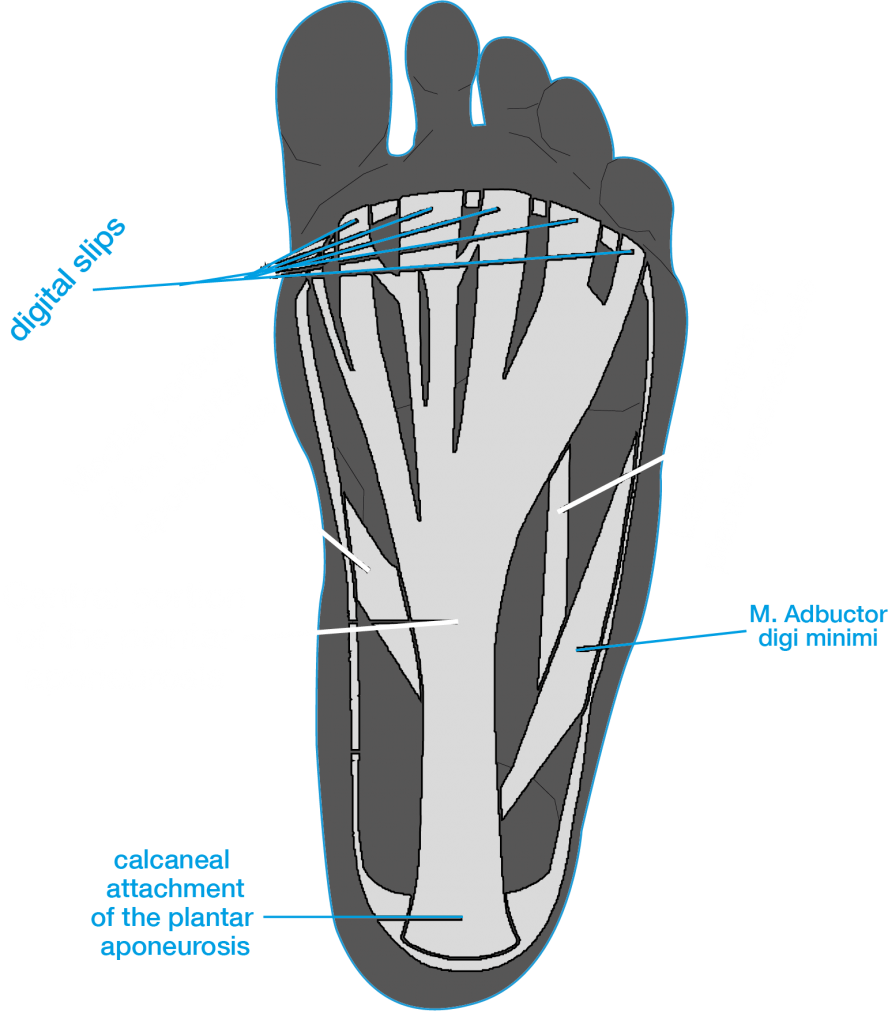

The plantar fascia is simply a thickened fibrous aponeurosis. An aponeurosis is simply a connective fibrous tissue similar to tendons however, in flat muscles or in flat surfaces (like the plantar of your foot), tendons are replaced by wide band with a wide area of attachment. That wide band is an aponeurosis, so if you hear someone talking about the plantar aponeurosis, you know it’s the plantar fascia they mean.

The plantar fascia has 3 bands (lateral medial and central) but it is only the central portion that originates from the medial calcaneal tuberosity on the undersurface of the calcaneus, or in the inferior heel region

Thing 2 - What is the function of the plantar fascia?

Thing 3 - What exactly is plantar fasciitis

Thing 4 - what makes the fascia prone to tearing?

The plantar fascia can tear due to several factors such as:

– limited range of motion for ankle dorsiflexion,

– obesity,

– work related weight bearing,

– calcaneal spurs,

– fat pad atrophy.

Moreover, it is important to understand that not only athletic populations develop this condition. For example, fat pad atrophy which is the reduction of the thickness of the adipose tissue at the bottom of the heel, increases at the age of 40, which will then expose the fascia to more biomechanical stress.

Furthermore, a change in work habits, such as spending more hours standing or walking, can aggravate symptoms or facilitate the development of the condition.

Thing 5 - how is plantar fasciitis diagnosed?

Patients also report that the heel pain reduces with increasing levels of activity but will worsen towards the end of the day. History taking is important because usually there has been a change in the volume of the physical activity or simply life changes that require more hours standing or walking.

Adding to the symptoms and patient history, there are physical examinations that can help with the diagnosis, such as:

– palpation of the proximal plantar fascia insertion,

– active and passive talocrural joint dorsiflexion,

– range of motion,

– the tarsal tunnel syndrome test,

– the windlass test, and

– the longitudinal arch angle.

Thing 6 - treatment options for plantar fasciitis

There are two type of interventions for plantar fasciitis, conservative or non-invasive and surgical or invasive. Non-invasive options are treatments such as orthoses (heels pads, plantar fascia groove, arch support), shock wave therapy, oral anti-inflammatory drugs, physiotherapy exercises, deep tissue massage, night splints, functional taping and steroid injections.

Invasive treatment options involves fascia release surgery whereby part of the fascia is cut from the calcaneus insertion to release tension. Surgery is a last resource solution and patients must be symptomatic for 12 to 24 months without relief with conventional methods.

References

Al-Boloushi, Z., López-Royo, M. P., Arian, M., Gómez-Trullén, E. M., & Herrero, P. (2019). Minimally invasive non-surgical management of plantar fasciitis: A systematic review. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 23(1), 122–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2018.05.002

Cole, C., Seto, C., & Gazewood, J. (2005). Plantar fasciitis: Evidence-based review of diagnosis and therapy. American Family Physician, 72(11), 2237–2242.

Mario Roxas. (2005). Plantar fasciitis: diagnosis and therapeutic considerations. Alternative Medicine Review, 10(2), 83–93.

Ricci, S. (2015). The venous system of the foot: anatomy, physiology and clinical aspects. Phlebolymphology, 22(2).

Thing, J., Maruthappu, M., & Rogers, J. (2012). Diagnosis and Management of Plantar Fasciitis in Primary Care. British Journal of General Practice, 62, 443–444. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp12X653769

Wilk, B. R., Fisher, K. L., & Gutierrez, W. (2000). Defective Running Shoes as a Contributing Factor in Plantar Fasciitis in a Triathlete. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 30(1), 21–31. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2000.30.1.21

Young, C. C., Rutherford, D. S., & Niedfeldt, M. W. (2001). Treatment of plantar fasciitis. American Family Physician, 63(3), 467–474.

About the author

Nuno Gama, PhD

Nuno is the founder of ORBIS LaB, a laboratory aimed at athletes and sports enthusiasts, based in Glasgow, UK. He is an expert in biomechanics and physiology and is an extremely approachable person. Nuno enjoys talking about science, life, and sports. Nuno is passionate about his family, his dogs, his guitars and his Rubiks’ cubes.

Related reading

6 things you should know about plantar fasciitis

Share on facebook Facebook Share on twitter Twitter Share on google Google+ Share on email Email Plantar fasciitis (PF) is an overuse injury characterised by